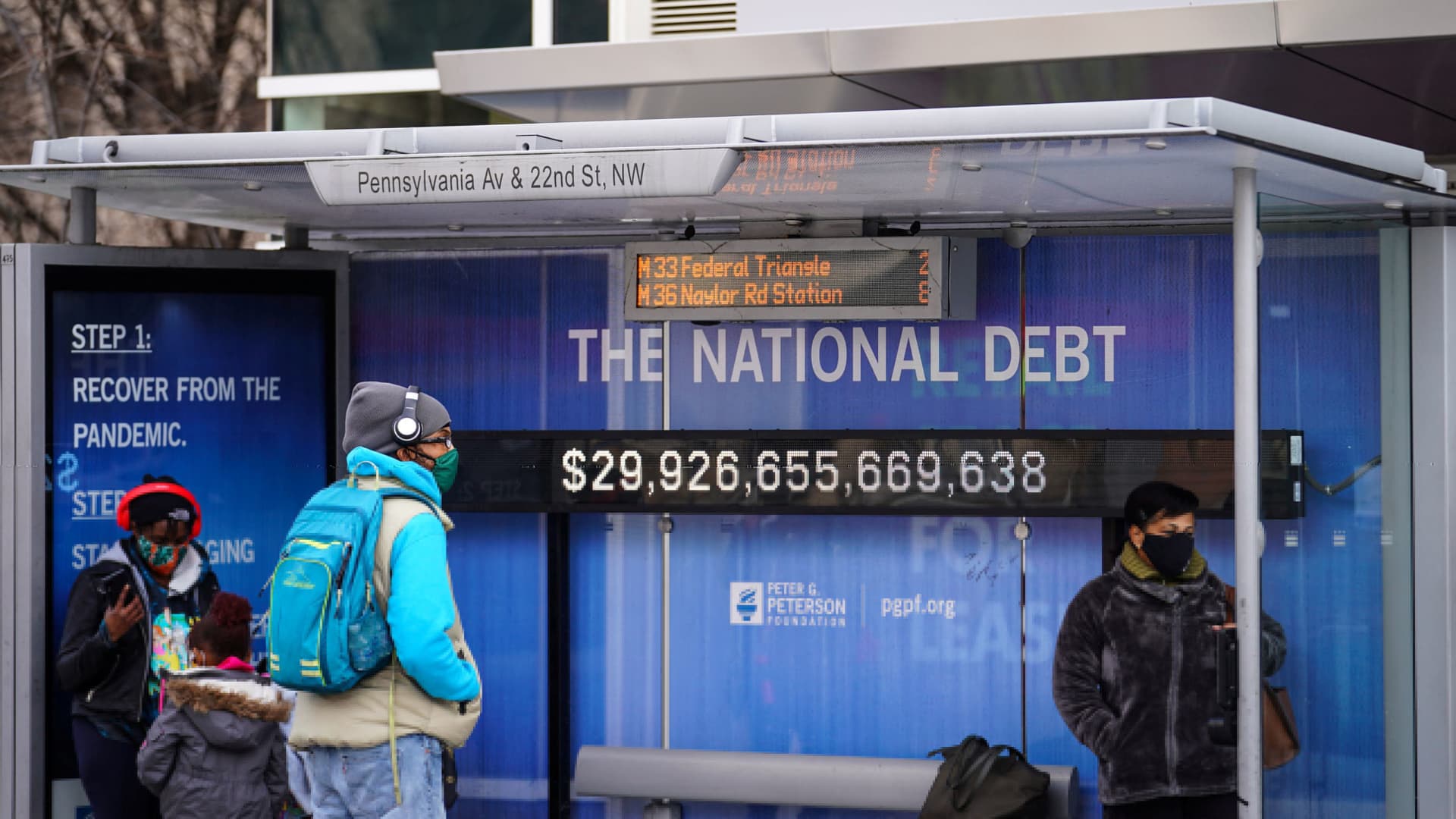

People wearing protective face masks wait at a bus stop with a display of the current national debt amid the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic in Washington, January 31, 2022.

Sarah Silbiger | Reuters

LONDON — Global sovereign debt is expected to climb by 9.5% to a record $71.6 trillion in 2022, according to a new report, while fresh borrowing is also broadly set to remain elevated.

In its second annual Sovereign Debt Index, published Wednesday, British asset manager Janus Henderson projected a 9.5% rise in global government debt, driven primarily by the U.S., Japan and China but with the vast majority of countries expected to increase borrowing.

Global government debt jumped 7.8% in 2021 to $65.4 trillion as every country assessed saw borrowing increase, while debt servicing costs dropped to a record low of $1.01 trillion, an effective interest rate of just 1.6%, the report said.

However, debt servicing costs are set to rise significantly in 2022, climbing around 14.5% on a constant-currency basis to $1.16 trillion.

The U.K. will feel the sharpest effect on the back of rising interest rates and the impact of surging inflation on the substantial quantities of U.K. index-linked debt, along with the costs associated with unwinding the Bank of England’s quantitative easing program.

“The pandemic has had a huge impact on government borrowing – and the after-effects are set to continue for some time yet. The tragedy unfolding in Ukraine is also likely to pressure Western governments to borrow more to fund increased defense spending,” said Bethany Payne, portfolio manager for global bonds at Janus Henderson.

Germany has already vowed to ramp up its defense spending to more than 2% of GDP in a sharp policy shift since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, along with committing 100 billion euros ($110 billion) to a fund for its armed services.

New sovereign borrowing is expected to reach $10.4 trillion in 2022, almost a third above the average prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, according to the latest global borrowing report from S&P Global Ratings published on Tuesday.

“We expect borrowing to stay elevated, owing to high debt-rollover needs, as well as fiscal policy normalization challenges posed by the pandemic, high inflation, and polarized social and political landscapes,” said S&P Global Ratings credit analyst Karen Vartapetov.

The ongoing conflict’s global macroeconomic repercussions are expected to exert further upward pressure on government funding needs, while tighter monetary conditions will increase government funding costs, the report highlighted.

This poses a further headache for sovereigns that have thus far struggled to reignite growth and cut reliance on foreign currency financing, and whose interest bills are already substantial.

In advanced economies, borrowing costs are expected to rise but likely remain at a level that will allow governments time for budget consolidation, S&P said, offering governments time for budget consolidation and focus on growth stimulating reforms.

Opportunities for investors

Convergence of monetary policy emerged as a theme during the first couple of years of the pandemic, as central banks cut interest rates to historic lows to help support ailing economies.

However, Janus Henderson noted that divergence is now emerging as a key theme, as central banks in the U.S., U.K., Europe, Canada and Australia look to tighten the policy strings to contain inflation, while China continues to try to stimulate the economy with a more accommodative policy stance.

This divergence offers opportunities for investors in short-dated bonds that are less susceptible to market conditions, Payne suggested, highlighting two locations in particular.

“One is China, which is actively engaging in loosening monetary policy, and Switzerland, which has more protection from inflationary pressure as energy takes up a much smaller percentage of its inflationary basket and their policy is tied, but lagging, to the ECB,” she said.

Janus Henderson also believes shorter-dated bonds look attractive at present relative to riskier long-term ones.

“When inflation and interest rates are rising, it is easy to dismiss fixed income as an asset class, particularly since bond valuations are relatively high by historical standards,” Payne said.

“But the valuation of many other asset classes is even higher and investor weightings to government bonds are relatively low, so there is a benefit in diversifying.”

What’s more, she argued, the markets have mostly priced in higher inflation expectations, so bonds bought today benefit from higher yields than they would have a few months ago.

Correction: The headline on this story has been updated with the correct figure for global government debt.